Boom Times for Mozambique

Only a couple of weeks ago Ruchir Sharma published a terrific article making the argument for the next seven breakout nations after the BRICS, which included two of my favorites, Thailand and Nigeria. But perhaps if he had waited for today’s news, maybe even Mozambique could make the list.

Only a couple of weeks ago Ruchir Sharma published a terrific article making the argument for the next seven breakout nations after the BRICS, which included two of my favorites, Thailand and Nigeria. But perhaps if he had waited for today’s news, maybe even Mozambique could make the list.

Today Eni has made yet another announcement of a considerable natural gas discovery of the coast of Mozambique, adding to numerous previous discoveries in recent years that could make the country a new energy leader on the continent in the near future.

But like most of Sharma’s breakout nations, Mozambique’s business opportunities are matched only by its considerable political risks, drawing some comparisons with the challenges for foreign investors in other Lusophone countries such as Angola.

After a decade-long civil war, Mozambique has making positive recovery, and showing a lot of promise in improving the grinding social conditions which have held back development behind the pace of many neighbors. Economic growth has averaged 8% over the past decade, and between 2012 and 2017 growth is expected to be maintained at around 7.5 percent.

Four of the five largest oil and gas discoveries in the world this year have been made the waters off Mozambique, according to Wood Mackenzie. The sheer quantity of hydrocarbons has the potential to transform the country into a major league player in gas exporting alongside world leaders like Qatar, provided the political stability can be achieved to offer foreign investors long term confidence.

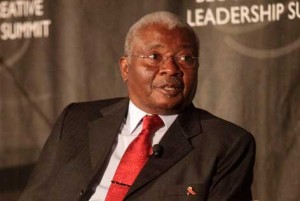

Previously under the regimes of Samora Machel and later Joachim Chissano, Mozambique failed to make much progress on its economical development goals. But despite complaints from many in the opposition over the quality of democratic competition in the country, the leadership of Armando Guebuza has shown capable of delivering tangible growth and investor confidence.

Guebuza, who has been president since 2005, has largely ruled unchallenged as the main opposition party, RENAMO (Resistência Nacional Moçambicana), was formed by the rebel faction from the civil war who continually threaten to return the country to armed violence if the elected government fails to make concessions toward their party.

Afonso Dhlakama, the leader of RENAMO, won 31.7% of the popular vote in the 2004 elections, and then 16.41% in the 2009 elections (the results of which are heavily disputed), signaling a weakening opposition but also a more fragmented electorate. For the time being, it appears that Guebuza’s FRELIMO party (Frente de Libertação de Moçambique), which has the backing of the South African leadership, will continue to dominate national politics and will likely seal another victory in 2014. The two biggest questions is whether or Guebuza will attempt to engineer a constitutional ammendment to allow for a third term in the next year, and if RENAMO in fact makes good on its promises to boycott elections and provoke violence.

The country is geographically blessed. Like Dar es Salaam, the ports of Maputo, Beir and Nacalaa are an essential link to inland Africa from the outside world. The instability of the civil war years denied them this opportunity to become trading hubs, not only to Mozambique but the rest of Southern Africa.

While the medium term risks are significant, for now many Mozambicans feel they are on a path to great recovery.

This year alone, the head of state inaugurating a new 107.5MW power station in July at Ressano Garcia, said coal and gas discoveries in the country would become “preponderant factors” in the country’s industrialisation. However, he calls for patience, in a way reminding his fellow countrymates of the all-time adage, “Rome was not built in a day.”

So far Statoil has farmed down a 25% working interest in its operated exploration licence offshore Mozambique to Tllow Oil plc creating numerous jobs for the population. The licence, which consists of two blocks under one licence agreement is located in area 2 and 5 offshore Mozambique in the Rovuma basin.

“The farm-down reflects the attractiveness of Statoil’s acreage in Mozambique and having Tullow onboard allows us to share the geological risk while retaining a significant working interest,” Nick Maden, senior vice president in Exploration international in Statoil, was recently quoted.

The blocks are located in a frontier area with a water depth varying between 300 and 2,400 metres. The area covers 7,800 square kilometres.

“Our presence in Mozambique is in line with Statoil’s exploration strategy focusing on early access in a prolific region. Large gas discoveries have recently been made north of our acreage and the prospectivity for hydrocarbons in the Statoil operated blocks is promising,” adds Maden.

However, these commercial terms of the transaction are kept as much confidential as they can but the government of Mozambique has granted approval subject to the Tax Authorities’ opinion on applicable transaction taxes.

There are substantial reserves of natural gas established in Mozambique and the country is likely to become a major producer of gas in the area in the medium term.

Records show that there are three onshore gas fields, Pande, Temane and Buzi-Divinhe.

There are three ports in Mozambique, Maputo, Beira, and Nacala which offer an economic supply corridor to neighbouring landlocked countries.

These activities make Mozambique a potentially strong economy in the region. For instance, the pipeline between Beira and Harare has been extended and is operating close to full capacity even with an expansion though the addition of pumping stations is underway.

While Mozambique is fledging with its oil and gas industry, the battles in the corridors of power have not spared this former Portuguese colony.

In October this year, President Guebuza sacked his Prime Minister in a surprise cabinet reshuffle replacing his presumed political successor with the little-known governor of Tete province, home to a massive coal mining investment boom.

Reuters reported that Prime Minister Aires Aly had been the president’s second-in-command and was being groomed to succeed Guebuza as president in the 2014 election. But his aspirations were crushed when the FRELIMO ousted him from its powerful Political Committee last month. Guebuza also replaced the tourism, education, youth and sports minister, leading many to conclude that indeed a third-term campaign may be underway.

The ruling party has been criticised recently for not yielding the benefits of its vast coal and gas deposits, leaving most Mozambicans to scrape by on an average $400 a year despite annual economic growth of around 7 percent in the last five years – an issue that is regularly raised by the opposition.

Altogether, Mozambique has all the ingredients to become an economic success story, but very few signs of the kind of institutional development that we would like to see in order to make this growth politically sustainable. If Guebuza can navigate the issues surrounding third term (or install a competent successor), and if RENAMO can be talked down from the sniper’s nest to take on a greater participation in the legislature if not compete for a real shot at the presidency, it would be inadvisable to get too excited about opening that office in Maputo. The next year should be very revealing.